Before the 1972 Summit Series, the face, heart, guts and soul of pro hockey was overwhelmingly Canadian. The NHL had expanded from the original six teams to fourteen, and most were based in the USA. But there were very few American players on the rosters. There were no Europeans. Not a Russian to be seen. When you tuned in to Hockey Night in Canada, you saw Canadians playing a freewheeling style of hockey. You’d see thrilling one-man end-to-end rushes. Booming slap shots from the point. Amazingly acrobatic saves. Bone-crunching hits. Bench-clearing brawls. Blood on the ice. It could be both beautiful and brutal in the space of a moment. You believed this was the very best hockey to be seen. Anywhere. We invented ice hockey. We knew Canada was the supreme hockey nation in the world.

The problem was that the world judged sports supremacy on international competition, and for hockey that meant the Olympics. And the Russians were the perpetual Gold Medal winners. Yes, the USA won it at Squaw Valley in 1964. But that was a glitch. It was always the Russians. Canada rarely made it to the podium. Canada did not even send a team to the ’72 Olympics, held earlier that year in Sapporo, Japan.

Why? In that era the concept of “amateur” was stringently observed and Canada’s best were playing as professionals in the NHL. They were barred from the Olympics. While most of the best Russian players were officially earning their paycheck as soldiers in the Soviet army. They were not paid to play hockey. But make no mistake, those elite Russian hockey players spent most of their year on the ice.

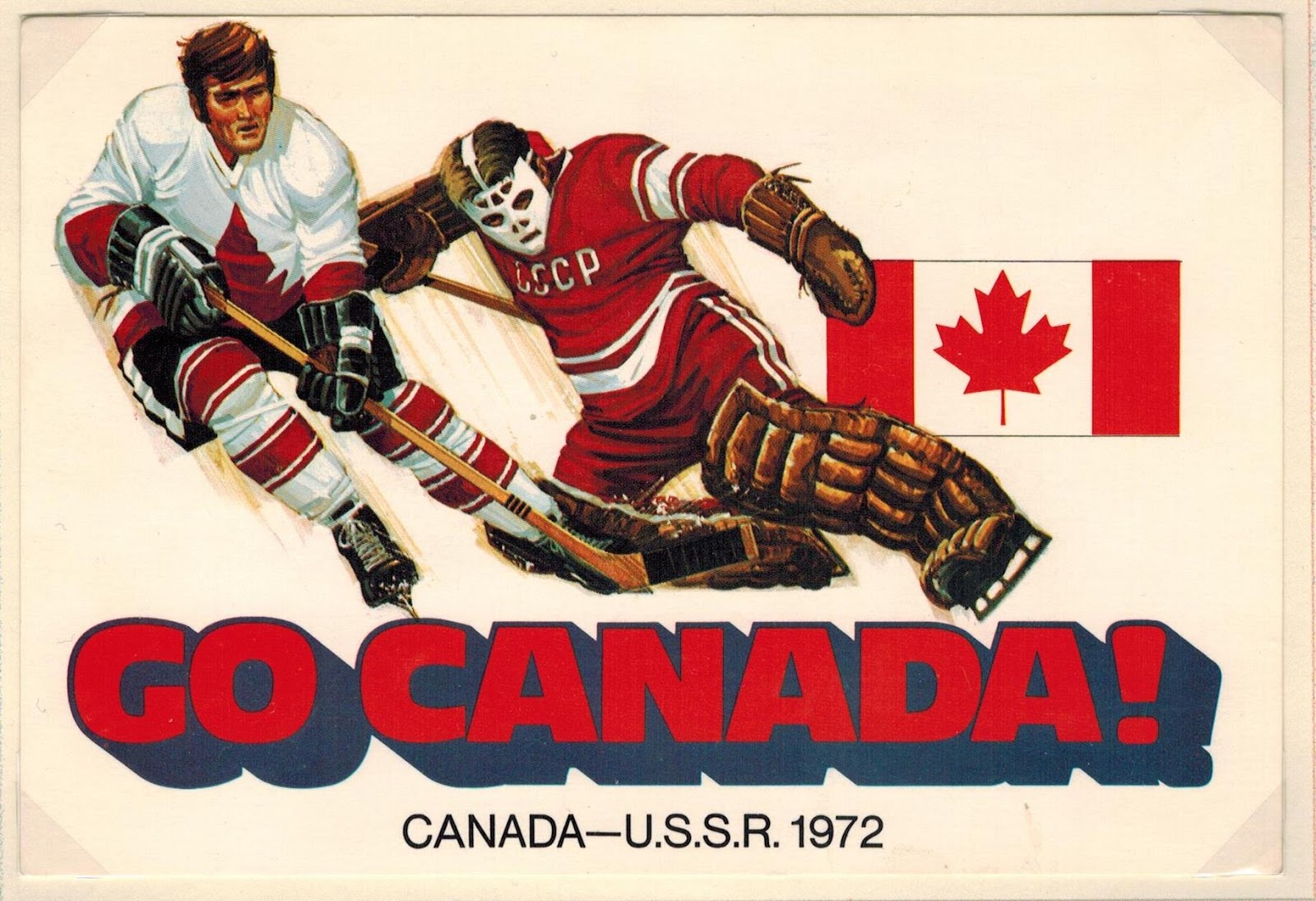

Dubbed simply the Canada-USSR series, the showdown was set for September, an eight-game series: four here, four there. No cup. Just bragging rights. It was about world hockey supremacy.

But it became much more than that. For Russia, winning gold at the Olympics always reverberated far beyond sporting accomplishment. It was a message to the world, saying this is the excellence modern Communism can produce. And we in Canada felt our team was playing for the very idea of Freedom.

We had to win. We had no doubt that we would.

It began in Montreal. The Russians wore mundane red jerseys with white lettering. Workaday, no flare. Canada wore billowy white with a huge stylized, deeper red maple leaf emerging from the waist. Nice design. The Russians wore red helmets. They appeared emotionless, robotic. Our guys did not yet wear helmets. They had personality. You could see their faces as they flew down the ice, their collar-length hair blowing free, those mutton-chop sideburns, bushy handlebar moustaches to match the times.

Normally hockey started in October, when the air is cooler. In early September, the Montreal weather was summery hot, humid. The old air conditioning and ice-making technology in the Forum at Ste. Catherine and Atwater could not meet the challenge. The heat got in. By the time that first game was over, there was a layer of foggy mist hovering just above the players’ heads. Seen on TV, these were ghostly images befitting a haunting, totally disorienting moment in the life of hockey-proud Canada.

Those colorless Russians displayed a style never seen on Hockey Night in Canada, moving up the ice as a tightly coordinated, brilliantly creative five-man unit, passing and cycling with (yes) military-like precision. And so fast! They were not as physically aggressive as our guys. Maybe they passed too much, waiting for the perfect shot. But they got their shots, and they overcame an early 2-0 deficit to beat us 7-3. Our team was left confused, frustrated, ineffective: clearly beaten. Canada was stunned.

We regrouped, got one back in Toronto, a 4-1 win. A tie in Winnipeg was another disappointment. Then a second loss in Vancouver. The crowd booed our guys off the ice. Team Canada assistant-captain Phil Esposito, league-leading scorer with the Boston Bruins, spoke publically, apologising for the awful result. At the same time, Esposito admonished the disappointed Canadian public for its lack of confidence.

- Phil Espisito

Confidence? This was our game and the Russians were beating us. It was like the world was falling apart!

The series moved to Russia. It was broadcast to Canada, and a contingent of Canadian fans made the trip. We saw them in the stands, waving flags, making noise. The Russian fans remained politely quiet. By official order. The feeling of our system versus their system was magnified. Hockey. Politics. Culture. National pride. Our national game. The players were carrying all this pressure.

Before it was over there would be more gut-wrenching surprises, both on and off the ice; some made us feel less than proud to be Canadian. And the final surprise was heart-stopping: Toronto Maple Leaf Paul Henderson’s historic game winner with thirty-four seconds to go in the final game, to give us the series.

Yes, we won. But it was obvious that we could no longer assume that our game was the best hockey in the world. To the contrary: we knew we had a lot of re-learning ahead of us.

Travelers bring gifts to their hosts as a sign of good will, something to remember us by. If the Russians brought us a glimpse of fast, disciplined, highly artistic hockey teamwork, we ultimately offered them a taste of Canadian grit, equal parts skill, heart, will and hockey pride.

Masterful goal tender Vladislav Tretiak, who after retirement would become president of the Russian Ice Hockey Federation, got it right: ‘Both teams won in 1972. It was a great series for all of hockey. The best that Russia had and the best of the NHL. The winner was the game of hockey.’